- Home

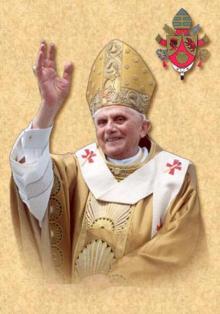

- Benedict XVI

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI Page 8

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI Read online

Page 8

An illustration of the significance of this problem is offered by the phenomenon of international tourism[141], which can be a major factor in economic development and cultural growth, but can also become an occasion for exploitation and moral degradation. The current situation offers unique opportunities for the economic aspects of development — that is to say the flow of money and the emergence of a significant amount of local enterprise — to be combined with the cultural aspects, chief among which is education. In many cases this is what happens, but in other cases international tourism has a negative educational impact both for the tourist and the local populace. The latter are often exposed to immoral or even perverted forms of conduct, as in the case of so-called sex tourism, to which many human beings are sacrificed even at a tender age. It is sad to note that this activity often takes place with the support of local governments, with silence from those in the tourists' countries of origin, and with the complicity of many of the tour operators. Even in less extreme cases, international tourism often follows a consumerist and hedonistic pattern, as a form of escapism planned in a manner typical of the countries of origin, and therefore not conducive to authentic encounter between persons and cultures. We need, therefore, to develop a different type of tourism that has the ability to promote genuine mutual understanding, without taking away from the element of rest and healthy recreation. Tourism of this type needs to increase, partly through closer coordination with the experience gained from international cooperation and enterprise for development.

62. Another aspect of integral human development that is worthy of attention is the phenomenon of migration. This is a striking phenomenon because of the sheer numbers of people involved, the social, economic, political, cultural and religious problems it raises, and the dramatic challenges it poses to nations and the international community. We can say that we are facing a social phenomenon of epoch-making proportions that requires bold, forward-looking policies of international cooperation if it is to be handled effectively. Such policies should set out from close collaboration between the migrants' countries of origin and their countries of destination; it should be accompanied by adequate international norms able to coordinate different legislative systems with a view to safeguarding the needs and rights of individual migrants and their families, and at the same time, those of the host countries. No country can be expected to address today's problems of migration by itself. We are all witnesses of the burden of suffering, the dislocation and the aspirations that accompany the flow of migrants. The phenomenon, as everyone knows, is difficult to manage; but there is no doubt that foreign workers, despite any difficulties concerning integration, make a significant contribution to the economic development of the host country through their labour, besides that which they make to their country of origin through the money they send home. Obviously, these labourers cannot be considered as a commodity or a mere workforce. They must not, therefore, be treated like any other factor of production. Every migrant is a human person who, as such, possesses fundamental, inalienable rights that must be respected by everyone and in every circumstance[142].

63. No consideration of the problems associated with development could fail to highlight the direct link between poverty and unemployment. In many cases, poverty results from a violation of the dignity of human work, either because work opportunities are limited (through unemployment or underemployment), or “because a low value is put on work and the rights that flow from it, especially the right to a just wage and to the personal security of the worker and his or her family”[143]. For this reason, on 1 May 2000 on the occasion of the Jubilee of Workers, my venerable predecessor Pope John Paul II issued an appeal for “a global coalition in favour of ‘decent work”'[144], supporting the strategy of the International Labour Organization. In this way, he gave a strong moral impetus to this objective, seeing it as an aspiration of families in every country of the world. What is meant by the word “decent” in regard to work? It means work that expresses the essential dignity of every man and woman in the context of their particular society: work that is freely chosen, effectively associating workers, both men and women, with the development of their community; work that enables the worker to be respected and free from any form of discrimination; work that makes it possible for families to meet their needs and provide schooling for their children, without the children themselves being forced into labour; work that permits the workers to organize themselves freely, and to make their voices heard; work that leaves enough room for rediscovering one's roots at a personal, familial and spiritual level; work that guarantees those who have retired a decent standard of living.

64. While reflecting on the theme of work, it is appropriate to recall how important it is that labour unions — which have always been encouraged and supported by the Church — should be open to the new perspectives that are emerging in the world of work. Looking to wider concerns than the specific category of labour for which they were formed, union organizations are called to address some of the new questions arising in our society: I am thinking, for example, of the complex of issues that social scientists describe in terms of a conflict between worker and consumer. Without necessarily endorsing the thesis that the central focus on the worker has given way to a central focus on the consumer, this would still appear to constitute new ground for unions to explore creatively. The global context in which work takes place also demands that national labour unions, which tend to limit themselves to defending the interests of their registered members, should turn their attention to those outside their membership, and in particular to workers in developing countries where social rights are often violated. The protection of these workers, partly achieved through appropriate initiatives aimed at their countries of origin, will enable trade unions to demonstrate the authentic ethical and cultural motivations that made it possible for them, in a different social and labour context, to play a decisive role in development. The Church's traditional teaching makes a valid distinction between the respective roles and functions of trade unions and politics. This distinction allows unions to identify civil society as the proper setting for their necessary activity of defending and promoting labour, especially on behalf of exploited and unrepresented workers, whose woeful condition is often ignored by the distracted eye of society.

65. Finance, therefore — through the renewed structures and operating methods that have to be designed after its misuse, which wreaked such havoc on the real economy — now needs to go back to being an instrument directed towards improved wealth creation and development. Insofar as they are instruments, the entire economy and finance, not just certain sectors, must be used in an ethical way so as to create suitable conditions for human development and for the development of peoples. It is certainly useful, and in some circumstances imperative, to launch financial initiatives in which the humanitarian dimension predominates. However, this must not obscure the fact that the entire financial system has to be aimed at sustaining true development. Above all, the intention to do good must not be considered incompatible with the effective capacity to produce goods. Financiers must rediscover the genuinely ethical foundation of their activity, so as not to abuse the sophisticated instruments which can serve to betray the interests of savers. Right intention, transparency, and the search for positive results are mutually compatible and must never be detached from one another. If love is wise, it can find ways of working in accordance with provident and just expediency, as is illustrated in a significant way by much of the experience of credit unions.

Both the regulation of the financial sector, so as to safeguard weaker parties and discourage scandalous speculation, and experimentation with new forms of finance, designed to support development projects, are positive experiences that should be further explored and encouraged, highlighting the responsibility of the investor. Furthermore, the experience of micro-finance, which has its roots in the thinking and activity of the civil humanists — I am thinking especially of the birth of pawnbroking �

�� should be strengthened and fine-tuned. This is all the more necessary in these days when financial difficulties can become severe for many of the more vulnerable sectors of the population, who should be protected from the risk of usury and from despair. The weakest members of society should be helped to defend themselves against usury, just as poor peoples should be helped to derive real benefit from micro-credit, in order to discourage the exploitation that is possible in these two areas. Since rich countries are also experiencing new forms of poverty, micro-finance can give practical assistance by launching new initiatives and opening up new sectors for the benefit of the weaker elements in society, even at a time of general economic downturn.

66. Global interconnectedness has led to the emergence of a new political power, that of consumers and their associations. This is a phenomenon that needs to be further explored, as it contains positive elements to be encouraged as well as excesses to be avoided. It is good for people to realize that purchasing is always a moral — and not simply economic — act. Hence the consumer has a specific social responsibility, which goes hand-in- hand with the social responsibility of the enterprise. Consumers should be continually educated[145] regarding their daily role, which can be exercised with respect for moral principles without diminishing the intrinsic economic rationality of the act of purchasing. In the retail industry, particularly at times like the present when purchasing power has diminished and people must live more frugally, it is necessary to explore other paths: for example, forms of cooperative purchasing like the consumer cooperatives that have been in operation since the nineteenth century, partly through the initiative of Catholics. In addition, it can be helpful to promote new ways of marketing products from deprived areas of the world, so as to guarantee their producers a decent return. However, certain conditions need to be met: the market should be genuinely transparent; the producers, as well as increasing their profit margins, should also receive improved formation in professional skills and technology; and finally, trade of this kind must not become hostage to partisan ideologies. A more incisive role for consumers, as long as they themselves are not manipulated by associations that do not truly represent them, is a desirable element for building economic democracy.

67. In the face of the unrelenting growth of global interdependence, there is a strongly felt need, even in the midst of a global recession, for a reform of the United Nations Organization, and likewise of economic institutions and international finance, so that the concept of the family of nations can acquire real teeth. One also senses the urgent need to find innovative ways of implementing the principle of the responsibility to protect[146] and of giving poorer nations an effective voice in shared decision-making. This seems necessary in order to arrive at a political, juridical and economic order which can increase and give direction to international cooperation for the development of all peoples in solidarity. To manage the global economy; to revive economies hit by the crisis; to avoid any deterioration of the present crisis and the greater imbalances that would result; to bring about integral and timely disarmament, food security and peace; to guarantee the protection of the environment and to regulate migration: for all this, there is urgent need of a true world political authority, as my predecessor Blessed John XXIII indicated some years ago. Such an authority would need to be regulated by law, to observe consistently the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity, to seek to establish the common good[147], and to make a commitment to securing authentic integral human development inspired by the values of charity in truth. Furthermore, such an authority would need to be universally recognized and to be vested with the effective power to ensure security for all, regard for justice, and respect for rights[148]. Obviously it would have to have the authority to ensure compliance with its decisions from all parties, and also with the coordinated measures adopted in various international forums. Without this, despite the great progress accomplished in various sectors, international law would risk being conditioned by the balance of power among the strongest nations. The integral development of peoples and international cooperation require the establishment of a greater degree of international ordering, marked by subsidiarity, for the management of globalization[149]. They also require the construction of a social order that at last conforms to the moral order, to the interconnection between moral and social spheres, and to the link between politics and the economic and civil spheres, as envisaged by the Charter of the United Nations.

CHAPTER SIX

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PEOPLES AND TECHNOLOGY

68. The development of peoples is intimately linked to the development of individuals. The human person by nature is actively involved in his own development. The development in question is not simply the result of natural mechanisms, since as everybody knows, we are all capable of making free and responsible choices. Nor is it merely at the mercy of our caprice, since we all know that we are a gift, not something self-generated. Our freedom is profoundly shaped by our being, and by its limits. No one shapes his own conscience arbitrarily, but we all build our own “I” on the basis of a “self” which is given to us. Not only are other persons outside our control, but each one of us is outside his or her own control. A person's development is compromised, if he claims to be solely responsible for producing what he becomes. By analogy, the development of peoples goes awry if humanity thinks it can re-create itself through the “wonders” of technology, just as economic development is exposed as a destructive sham if it relies on the “wonders” of finance in order to sustain unnatural and consumerist growth. In the face of such Promethean presumption, we must fortify our love for a freedom that is not merely arbitrary, but is rendered truly human by acknowledgment of the good that underlies it. To this end, man needs to look inside himself in order to recognize the fundamental norms of the natural moral law which God has written on our hearts.

69. The challenge of development today is closely linked to technological progress, with its astounding applications in the field of biology. Technology — it is worth emphasizing — is a profoundly human reality, linked to the autonomy and freedom of man. In technology we express and confirm the hegemony of the spirit over matter. “The human spirit, ‘increasingly free of its bondage to creatures, can be more easily drawn to the worship and contemplation of the Creator'”[150]. Technology enables us to exercise dominion over matter, to reduce risks, to save labour, to improve our conditions of life. It touches the heart of the vocation of human labour: in technology, seen as the product of his genius, man recognizes himself and forges his own humanity. Technology is the objective side of human action[151] whose origin and raison d'etre is found in the subjective element: the worker himself. For this reason, technology is never merely technology. It reveals man and his aspirations towards development, it expresses the inner tension that impels him gradually to overcome material limitations. Technology, in this sense, is a response to God's command to till and to keep the land (cf. Gen 2:15) that he has entrusted to humanity, and it must serve to reinforce the covenant between human beings and the environment, a covenant that should mirror God's creative love.

70. Technological development can give rise to the idea that technology is self-sufficient when too much attention is given to the “how” questions, and not enough to the many “why” questions underlying human activity. For this reason technology can appear ambivalent. Produced through human creativity as a tool of personal freedom, technology can be understood as a manifestation of absolute freedom, the freedom that seeks to prescind from the limits inherent in things. The process of globalization could replace ideologies with technology[152], allowing the latter to become an ideological power that threatens to confine us within an a priori that holds us back from encountering being and truth. Were that to happen, we would all know, evaluate and make decisions about our life situations from within a technocratic cultural perspective to which we would belong structurally, without ever being able to discover a meaning that is not of our own making. The “technical” wo

rldview that follows from this vision is now so dominant that truth has come to be seen as coinciding with the possible. But when the sole criterion of truth is efficiency and utility, development is automatically denied. True development does not consist primarily in “doing”. The key to development is a mind capable of thinking in technological terms and grasping the fully human meaning of human activities, within the context of the holistic meaning of the individual's being. Even when we work through satellites or through remote electronic impulses, our actions always remain human, an expression of our responsible freedom. Technology is highly attractive because it draws us out of our physical limitations and broadens our horizon. But human freedom is authentic only when it responds to the fascination of technology with decisions that are the fruit of moral responsibility. Hence the pressing need for formation in an ethically responsible use of technology. Moving beyond the fascination that technology exerts, we must reappropriate the true meaning of freedom, which is not an intoxication with total autonomy, but a response to the call of being, beginning with our own personal being.

71. This deviation from solid humanistic principles that a technical mindset can produce is seen today in certain technological applications in the fields of development and peace. Often the development of peoples is considered a matter of financial engineering, the freeing up of markets, the removal of tariffs, investment in production, and institutional reforms — in other words, a purely technical matter. All these factors are of great importance, but we have to ask why technical choices made thus far have yielded rather mixed results. We need to think hard about the cause. Development will never be fully guaranteed through automatic or impersonal forces, whether they derive from the market or from international politics. Development is impossible without upright men and women, without financiers and politicians whose consciences are finely attuned to the requirements of the common good. Both professional competence and moral consistency are necessary. When technology is allowed to take over, the result is confusion between ends and means, such that the sole criterion for action in business is thought to be the maximization of profit, in politics the consolidation of power, and in science the findings of research. Often, underneath the intricacies of economic, financial and political interconnections, there remain misunderstandings, hardships and injustice. The flow of technological know-how increases, but it is those in possession of it who benefit, while the situation on the ground for the peoples who live in its shadow remains unchanged: for them there is little chance of emancipation.

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI