- Home

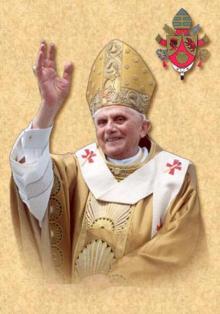

- Benedict XVI

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI Page 3

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI Read online

Page 3

22. Today the picture of development has many overlapping layers. The actors and the causes in both underdevelopment and development are manifold, the faults and the merits are differentiated. This fact should prompt us to liberate ourselves from ideologies, which often oversimplify reality in artificial ways, and it should lead us to examine objectively the full human dimension of the problems. As John Paul II has already observed, the demarcation line between rich and poor countries is no longer as clear as it was at the time of Populorum Progressio[55]. The world's wealth is growing in absolute terms, but inequalities are on the increase. In rich countries, new sectors of society are succumbing to poverty and new forms of poverty are emerging. In poorer areas some groups enjoy a sort of “superdevelopment” of a wasteful and consumerist kind which forms an unacceptable contrast with the ongoing situations of dehumanizing deprivation. “The scandal of glaring inequalities”[56] continues. Corruption and illegality are unfortunately evident in the conduct of the economic and political class in rich countries, both old and new, as well as in poor ones. Among those who sometimes fail to respect the human rights of workers are large multinational companies as well as local producers. International aid has often been diverted from its proper ends, through irresponsible actions both within the chain of donors and within that of the beneficiaries. Similarly, in the context of immaterial or cultural causes of development and underdevelopment, we find these same patterns of responsibility reproduced. On the part of rich countries there is excessive zeal for protecting knowledge through an unduly rigid assertion of the right to intellectual property, especially in the field of health care. At the same time, in some poor countries, cultural models and social norms of behaviour persist which hinder the process of development.

23. Many areas of the globe today have evolved considerably, albeit in problematical and disparate ways, thereby taking their place among the great powers destined to play important roles in the future. Yet it should be stressed that progress of a merely economic and technological kind is insufficient. Development needs above all to be true and integral. The mere fact of emerging from economic backwardness, though positive in itself, does not resolve the complex issues of human advancement, neither for the countries that are spearheading such progress, nor for those that are already economically developed, nor even for those that are still poor, which can suffer not just through old forms of exploitation, but also from the negative consequences of a growth that is marked by irregularities and imbalances.

After the collapse of the economic and political systems of the Communist countries of Eastern Europe and the end of the so-called opposing blocs, a complete re-examination of development was needed. Pope John Paul II called for it, when in 1987 he pointed to the existence of these blocs as one of the principal causes of underdevelopment[57], inasmuch as politics withdrew resources from the economy and from the culture, and ideology inhibited freedom. Moreover, in 1991, after the events of 1989, he asked that, in view of the ending of the blocs, there should be a comprehensive new plan for development, not only in those countries, but also in the West and in those parts of the world that were in the process of evolving[58]. This has been achieved only in part, and it is still a real duty that needs to be discharged, perhaps by means of the choices that are necessary to overcome current economic problems.

24. The world that Paul VI had before him — even though society had already evolved to such an extent that he could speak of social issues in global terms — was still far less integrated than today's world. Economic activity and the political process were both largely conducted within the same geographical area, and could therefore feed off one another. Production took place predominantly within national boundaries, and financial investments had somewhat limited circulation outside the country, so that the politics of many States could still determine the priorities of the economy and to some degree govern its performance using the instruments at their disposal. Hence Populorum Progressio assigned a central, albeit not exclusive, role to “public authorities”[59].

In our own day, the State finds itself having to address the limitations to its sovereignty imposed by the new context of international trade and finance, which is characterized by increasing mobility both of financial capital and means of production, material and immaterial. This new context has altered the political power of States.

Today, as we take to heart the lessons of the current economic crisis, which sees the State's public authorities directly involved in correcting errors and malfunctions, it seems more realistic to re-evaluate their role and their powers, which need to be prudently reviewed and remodelled so as to enable them, perhaps through new forms of engagement, to address the challenges of today's world. Once the role of public authorities has been more clearly defined, one could foresee an increase in the new forms of political participation, nationally and internationally, that have come about through the activity of organizations operating in civil society; in this way it is to be hoped that the citizens' interest and participation in the res publica will become more deeply rooted.

25. From the social point of view, systems of protection and welfare, already present in many countries in Paul VI's day, are finding it hard and could find it even harder in the future to pursue their goals of true social justice in today's profoundly changed environment. The global market has stimulated first and foremost, on the part of rich countries, a search for areas in which to outsource production at low cost with a view to reducing the prices of many goods, increasing purchasing power and thus accelerating the rate of development in terms of greater availability of consumer goods for the domestic market. Consequently, the market has prompted new forms of competition between States as they seek to attract foreign businesses to set up production centres, by means of a variety of instruments, including favourable fiscal regimes and deregulation of the labour market. These processes have led to a downsizing of social security systems as the price to be paid for seeking greater competitive advantage in the global market, with consequent grave danger for the rights of workers, for fundamental human rights and for the solidarity associated with the traditional forms of the social State. Systems of social security can lose the capacity to carry out their task, both in emerging countries and in those that were among the earliest to develop, as well as in poor countries. Here budgetary policies, with cuts in social spending often made under pressure from international financial institutions, can leave citizens powerless in the face of old and new risks; such powerlessness is increased by the lack of effective protection on the part of workers' associations. Through the combination of social and economic change, trade union organizations experience greater difficulty in carrying out their task of representing the interests of workers, partly because Governments, for reasons of economic utility, often limit the freedom or the negotiating capacity of labour unions. Hence traditional networks of solidarity have more and more obstacles to overcome. The repeated calls issued within the Church's social doctrine, beginning with Rerum Novarum[60], for the promotion of workers' associations that can defend their rights must therefore be honoured today even more than in the past, as a prompt and far-sighted response to the urgent need for new forms of cooperation at the international level, as well as the local level.

The mobility of labour, associated with a climate of deregulation, is an important phenomenon with certain positive aspects, because it can stimulate wealth production and cultural exchange. Nevertheless, uncertainty over working conditions caused by mobility and deregulation, when it becomes endemic, tends to create new forms of psychological instability, giving rise to difficulty in forging coherent life-plans, including that of marriage. This leads to situations of human decline, to say nothing of the waste of social resources. In comparison with the casualties of industrial society in the past, unemployment today provokes new forms of economic marginalization, and the current crisis can only make this situation worse. Being out of work or dependent on public or private assistance for a prol

onged period undermines the freedom and creativity of the person and his family and social relationships, causing great psychological and spiritual suffering. I would like to remind everyone, especially governments engaged in boosting the world's economic and social assets, that the primary capital to be safeguarded and valued is man, the human person in his or her integrity: “Man is the source, the focus and the aim of all economic and social life”[61].

26. On the cultural plane, compared with Paul VI's day, the difference is even more marked. At that time cultures were relatively well defined and had greater opportunity to defend themselves against attempts to merge them into one. Today the possibilities of interaction between cultures have increased significantly, giving rise to new openings for intercultural dialogue: a dialogue that, if it is to be effective, has to set out from a deep-seated knowledge of the specific identity of the various dialogue partners. Let it not be forgotten that the increased commercialization of cultural exchange today leads to a twofold danger. First, one may observe a cultural eclecticism that is often assumed uncritically: cultures are simply placed alongside one another and viewed as substantially equivalent and interchangeable. This easily yields to a relativism that does not serve true intercultural dialogue; on the social plane, cultural relativism has the effect that cultural groups coexist side by side, but remain separate, with no authentic dialogue and therefore with no true integration. Secondly, the opposite danger exists, that of cultural levelling and indiscriminate acceptance of types of conduct and life-styles. In this way one loses sight of the profound significance of the culture of different nations, of the traditions of the various peoples, by which the individual defines himself in relation to life's fundamental questions[62]. What eclecticism and cultural levelling have in common is the separation of culture from human nature. Thus, cultures can no longer define themselves within a nature that transcends them[63], and man ends up being reduced to a mere cultural statistic. When this happens, humanity runs new risks of enslavement and manipulation.

27. Life in many poor countries is still extremely insecure as a consequence of food shortages, and the situation could become worse: hunger still reaps enormous numbers of victims among those who, like Lazarus, are not permitted to take their place at the rich man's table, contrary to the hopes expressed by Paul VI[64]. Feed the hungry (cf. Mt 25: 35, 37, 42) is an ethical imperative for the universal Church, as she responds to the teachings of her Founder, the Lord Jesus, concerning solidarity and the sharing of goods. Moreover, the elimination of world hunger has also, in the global era, become a requirement for safeguarding the peace and stability of the planet. Hunger is not so much dependent on lack of material things as on shortage of social resources, the most important of which are institutional. What is missing, in other words, is a network of economic institutions capable of guaranteeing regular access to sufficient food and water for nutritional needs, and also capable of addressing the primary needs and necessities ensuing from genuine food crises, whether due to natural causes or political irresponsibility, nationally and internationally. The problem of food insecurity needs to be addressed within a long-term perspective, eliminating the structural causes that give rise to it and promoting the agricultural development of poorer countries. This can be done by investing in rural infrastructures, irrigation systems, transport, organization of markets, and in the development and dissemination of agricultural technology that can make the best use of the human, natural and socio-economic resources that are more readily available at the local level, while guaranteeing their sustainability over the long term as well. All this needs to be accomplished with the involvement of local communities in choices and decisions that affect the use of agricultural land. In this perspective, it could be useful to consider the new possibilities that are opening up through proper use of traditional as well as innovative farming techniques, always assuming that these have been judged, after sufficient testing, to be appropriate, respectful of the environment and attentive to the needs of the most deprived peoples. At the same time, the question of equitable agrarian reform in developing countries should not be ignored. The right to food, like the right to water, has an important place within the pursuit of other rights, beginning with the fundamental right to life. It is therefore necessary to cultivate a public conscience that considers food and access to water as universal rights of all human beings, without distinction or discrimination[65]. It is important, moreover, to emphasize that solidarity with poor countries in the process of development can point towards a solution of the current global crisis, as politicians and directors of international institutions have begun to sense in recent times. Through support for economically poor countries by means of financial plans inspired by solidarity — so that these countries can take steps to satisfy their own citizens' demand for consumer goods and for development — not only can true economic growth be generated, but a contribution can be made towards sustaining the productive capacities of rich countries that risk being compromised by the crisis.

28. One of the most striking aspects of development in the present day is the important question of respect for life, which cannot in any way be detached from questions concerning the development of peoples. It is an aspect which has acquired increasing prominence in recent times, obliging us to broaden our concept of poverty[66] and underdevelopment to include questions connected with the acceptance of life, especially in cases where it is impeded in a variety of ways.

Not only does the situation of poverty still provoke high rates of infant mortality in many regions, but some parts of the world still experience practices of demographic control, on the part of governments that often promote contraception and even go so far as to impose abortion. In economically developed countries, legislation contrary to life is very widespread, and it has already shaped moral attitudes and praxis, contributing to the spread of an anti-birth mentality; frequent attempts are made to export this mentality to other States as if it were a form of cultural progress.

Some non-governmental Organizations work actively to spread abortion, at times promoting the practice of sterilization in poor countries, in some cases not even informing the women concerned. Moreover, there is reason to suspect that development aid is sometimes linked to specific health-care policies which de facto involve the imposition of strong birth control measures. Further grounds for concern are laws permitting euthanasia as well as pressure from lobby groups, nationally and internationally, in favour of its juridical recognition.

Openness to life is at the centre of true development. When a society moves towards the denial or suppression of life, it ends up no longer finding the necessary motivation and energy to strive for man's true good. If personal and social sensitivity towards the acceptance of a new life is lost, then other forms of acceptance that are valuable for society also wither away[67]. The acceptance of life strengthens moral fibre and makes people capable of mutual help. By cultivating openness to life, wealthy peoples can better understand the needs of poor ones, they can avoid employing huge economic and intellectual resources to satisfy the selfish desires of their own citizens, and instead, they can promote virtuous action within the perspective of production that is morally sound and marked by solidarity, respecting the fundamental right to life of every people and every individual.

29. There is another aspect of modern life that is very closely connected to development: the denial of the right to religious freedom. I am not referring simply to the struggles and conflicts that continue to be fought in the world for religious motives, even if at times the religious motive is merely a cover for other reasons, such as the desire for domination and wealth. Today, in fact, people frequently kill in the holy name of God, as both my predecessor John Paul II and I myself have often publicly acknowledged and lamented[68]. Violence puts the brakes on authentic development and impedes the evolution of peoples towards greater socio-economic and spiritual well-being. This applies especially to terrorism motivated by fundamentalism[69], which generates

grief, destruction and death, obstructs dialogue between nations and diverts extensive resources from their peaceful and civil uses.

Yet it should be added that, as well as religious fanaticism that in some contexts impedes the exercise of the right to religious freedom, so too the deliberate promotion of religious indifference or practical atheism on the part of many countries obstructs the requirements for the development of peoples, depriving them of spiritual and human resources. God is the guarantor of man's true development, inasmuch as, having created him in his image, he also establishes the transcendent dignity of men and women and feeds their innate yearning to “be more”. Man is not a lost atom in a random universe[70]: he is God's creature, whom God chose to endow with an immortal soul and whom he has always loved. If man were merely the fruit of either chance or necessity, or if he had to lower his aspirations to the limited horizon of the world in which he lives, if all reality were merely history and culture, and man did not possess a nature destined to transcend itself in a supernatural life, then one could speak of growth, or evolution, but not development. When the State promotes, teaches, or actually imposes forms of practical atheism, it deprives its citizens of the moral and spiritual strength that is indispensable for attaining integral human development and it impedes them from moving forward with renewed dynamism as they strive to offer a more generous human response to divine love[71]. In the context of cultural, commercial or political relations, it also sometimes happens that economically developed or emerging countries export this reductive vision of the person and his destiny to poor countries. This is the damage that “superdevelopment”[72] causes to authentic development when it is accompanied by “moral underdevelopment”[73].

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI

Caritas in Veritate - Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI